What do we think about this? Wait...before you respond, take a look at this paper, authored by Parkland Professor Erin Wilding-Martin:

Now, the article:

May 7, 2013

High Schools Set Up Community-College Students to Fail, Report Says

By Katherine Mangan

Community

colleges' academic expectations are "shockingly low," but students

still struggle to meet them, in part because high-school graduation

standards are too lax in English and too rigid in mathematics,

according to a study released on Tuesday by the National Center on

Education and the Economy.

Students

entering community colleges have poor reading and writing skills and a

shaky grasp of advanced math concepts that most of them will never

need, the study found.

The

center, a nonprofit organization dedicated to college readiness,

examined the math and English skills needed to succeed in first-year

community-college courses. In a report on the study, the authors

acknowledge that their findings are controversial, especially their

conclusion that not all students need a second year of algebra.

A

typical high-school math sequence includes geometry, a second year of

algebra, precalculus, and calculus, the authors note. They say that

less than 5 percent of American workers need calculus and that high

schools should offer alternative pathways including options like

statistics, data analysis, and applied geometry.

In

math, students are rushed through middle-school courses without fully

grasping the concepts in order to get to more-advanced material, the

study concludes.

"It's

kind of like saying the League of Nations is more important to study

than the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence because it

comes later," Phil Daro, co-chair of the study's mathematics panel,

said on Tuesday during a daylong discussion of the findings.

What

students need to succeed in entry-level college classes is

middle-school math, especially arithmetic, ratio, proportion,

expressions, and simple equations, the report says.

The

authors insist that they aren't calling for weaker standards, but

simply more flexibility, so that students who are interested in

vocational fields can take applied math that would be more useful to

them.

The entire sequence, from secondary education through college, needs to be better aligned, they say.

"You

think of community colleges as Grade 13, and that kids go through a

progression with each year building on the previous year," said Marc S.

Tucker, president of the national center. "What I see is kids leaving

the 12th grade, going to community college, and beginning back in

middle school. That's not a progression. That's going backwards."

A Retreat to Tracking?

The

study focused on community colleges because they offer a gateway to

four-year colleges for a large and increasing proportion of students,

and provide the bulk of vocational and technical education offered in

the United States. About 45 percent of American college students are

enrolled in such colleges.

The

study was guided by panels of experts in the subject matter, and was

overseen by an advisory committee that included leading

psychometricians, cognitive scientists, and curriculum experts. The

project was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The

authors selected seven diverse states and randomly chose a community

college in each one, focusing on eight popular programs preparing

students for careers and for transfer to four-year colleges. They

examined textbooks, assigned work, tests, and grades.

The

argument that high-school math requirements are too rigid has prompted

lawmakers in some states to recommend making it easier for students to

pursue vocational paths. In Texas, for instance, lawmakers are debating

proposals that would allow some students to graduate without completing

a second year of algebra.

The

changes are supported by industry and trade groups that are having

trouble finding enough skilled workers but are opposed by those who

worry about a return to the days when low-income and minority students

were routinely tracked into vocational careers. Loosening graduation

requirements would mark a retreat, they argue, from the decades-long

national push toward tougher graduation requirements at high schools.

Turning

to English, the study found that instructors often assume that students

can't understand their textbooks, even though they're written at an

11th- or 12th-grade level. They compensate by using videos, flash

cards, and PowerPoint presentations to summarize the material.

Most

introductory college classes demand little writing, and when it is

required, "instructors tend to have very low expectations for

grammatical accuracy, appropriate diction, clarity of expression,

reasoning, and the ability to present a logical argument or offer

evidence in support of claims."

Across

the curriculum, "the default is short-form assignments that require

neither breadth nor depth of knowledge," the report says. The exception

was in English-composition classes, where students were typically

challenged.

Raising

the bar too quickly for college classes would be a mistake, according

to the study, because so many students are unable to handle current

course levels and end up in remedial classes.

Ill Prepared for College

Walter

G. Bumphus, president of the American Association of Community

Colleges, said the report underscores issues that are already being

dealt with by the association's 21st-Century Commission on the Future

of Community Colleges, including the problem that "far too many

students are coming to community colleges ill prepared to do

college-level work, especially in foundational math and English."

The

president of a nonprofit group that is working to raise academic

standards said the report reinforces the importance of Common Core

State Standards that have been approved by 45 states and the District

of Columbia.

The

revamped version of second-year algebra in those standards includes

more emphasis on modeling and drawing inferences and conclusions from

data—skills that are relevant to all students, said Michael Cohen,

president of Achieve.

Scrapping

the course requirement altogether could hurt low-income and minority

students who would be more likely to opt out and thus be less prepared

for college, he said. "We don't really want to set the expectations for

high-school students at a level that reflects what community colleges

currently demand," he added. "That's not setting the bar very high."

This news article is reprinted from The Chronicle of Higher Education at:

# # # # # #

(23,824)

(23,824)

http://www.cftl.org/documents/2012/CFTL_MathPatterns_Main_Report.pdf outlines how students who have to repeat a class in middle school tend to end up not doing well in math for the duration. Essentially, it's not when you take what that matters, but how well you are prepared for it when you take it.

ReplyDeletePeople seem to assume that a conceptual gap is the same as an inability to learn math... when often what is needed is to fill in that gap, so teh student can reach new heights.

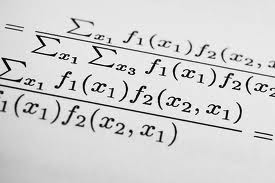

To follow up on my article link (which was written during the Fall of 2012), our pilot sections went very well this semester and we are excited to go full-scale this coming fall. We have created a course with more relevant content for students who do not need to prepare for calculus, but we have also maintained very high expectations. For the most part, students have really risen to the challenge and I have seen real engagement with some rather complicated math investigations. Very exciting.

ReplyDeleteThis article should be sent to the school boards in the surrounding communities. Unit 4 school is now using standardized grading and homework doesn't count towards the grade. This is in the high schools. That is scary!! There will be a large number of students that are not prepared for college or vocational schools.

ReplyDelete